How a Silicon Valley firm became one of the most influential—and controversial—forces in modern law enforcement and government surveillance.

The Company Behind the Curtain

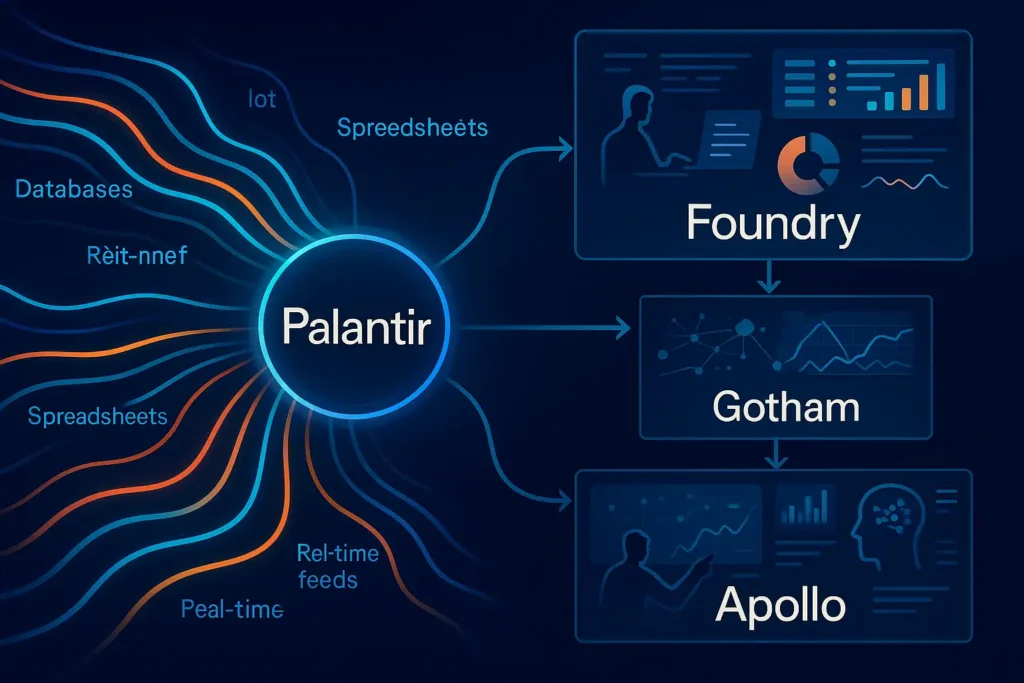

Palantir Technologies does not look like a typical surveillance company. It doesn’t sell cameras. It doesn’t tap phone lines. It doesn’t need to. Its power lies elsewhere: turning fragmented data into a single operational picture.

Founded in the mid-2000s and heavily funded in its early years by U.S. intelligence-linked venture capital, Palantir built its reputation by serving defense, intelligence, and law-enforcement agencies that were drowning in data but starved for insight. Its flagship government platform, Gotham, is now widely used by federal, state, and local agencies. Its commercial counterpart, Foundry, brings the same data-fusion logic to corporations, hospitals, and financial institutions.

Palantir’s business model is simple—and consequential: take data that already exists, integrate it, and make it actionable.

“Palantir doesn’t collect your data. It makes other people’s data dangerous.”

How the Data Fusion Pipeline Works

Palantir’s technology is best understood as a pipeline—one that transforms scattered records into operational intelligence.

1. Ingest

Agencies feed Palantir data they already possess or can legally obtain. This may include:

- Arrest and booking records

- DMV and licensing data

- Court filings and warrants

- Immigration and border records

- Phone numbers, addresses, and identifiers

- Purchased commercial datasets

- Open-source intelligence and tips

Palantir does not typically originate this data. It absorbs it.

2. Normalize

Different systems store data differently. Gotham standardizes formats so names, dates, locations, and identifiers can be compared across databases that were never designed to talk to each other.

3. Resolve Identities

This is the most powerful—and risky—step. Palantir tools attempt to determine whether “John Smith,” “J. Smith,” and a phone number belong to the same person. Errors here don’t stay small; they propagate.

4. Link and Model

People, places, vehicles, phones, and events become nodes in a graph. Associations emerge:

- Who knows whom

- Who was where and when

- Who traveled together

- Who shares addresses, devices, or contacts

5. Operationalize

The data is no longer passive. Investigators receive dashboards, alerts, timelines, and “case views” that guide real-world decisions—raids, arrests, deportations, surveillance priorities.

“At scale, data fusion turns coincidence into suspicion.”

From Crime to Immigration to ‘Everything Else’

Palantir’s tools are marketed as neutral. In practice, they follow power.

Law Enforcement

Police departments use Gotham for investigations, cold cases, and intelligence analysis. What once took weeks of manual cross-checking can now take minutes.

Immigration Enforcement

Palantir’s role in U.S. immigration enforcement has drawn sustained scrutiny. Systems built on its platforms have been used to:

- Track individuals across agencies

- Build deportation cases

- Integrate travel, identity, and administrative records

Civil-liberties groups argue this enables surveillance-by-default, where entire communities become data-mapped populations.

Beyond Policing

The same tools now appear in:

- Military logistics and targeting support

- Pandemic response and hospital capacity planning

- Corporate workforce monitoring

- Financial fraud detection

The domain changes. The data model stays the same.

Key Controversies

1. Function Creep

Tools deployed for “serious crime” often expand quietly into routine enforcement. Once the system exists, limiting its use becomes a policy problem—not a technical one.

2. Invisible Errors

When fused data is wrong, it doesn’t look wrong. A mistaken association can appear authoritative simply because it’s visualized, linked, and machine-endorsed.

3. Bias at Scale

Even when race or religion isn’t explicitly tracked, proxies—location, associations, language, prior police contact—can reproduce structural bias automatically.

4. Vendor Lock-In

Palantir often embeds engineers alongside agencies. Critics argue this deep integration makes oversight harder and exit unlikely.

“Surveillance doesn’t need to be malicious to be harmful—it only needs to be permanent.”

Palantir’s Defense

Palantir maintains that:

- Customers control what data is ingested

- Strong access controls and audit logs exist

- The platform supports lawful, governed use

In other words: we build the tool; others decide how to use it.

That argument has a long history in technology—and an equally long list of consequences.

What Oversight Should Look Like

If data-fusion platforms are going to remain embedded in government, oversight must move beyond press releases and procurement contracts.

Meaningful oversight would include:

- Public disclosure of what datasets are integrated

- Independent audits of accuracy and bias

- Clear use limitations written into law, not policy memos

- Due-process protections for individuals flagged by analytics

- Sunset clauses that force reevaluation instead of permanent expansion

Most importantly, oversight must assume misuse is possible, not hypothetical.

“A system powerful enough to find terrorists is powerful enough to map ordinary lives.”

Palantir represents a turning point in governance. It shows what happens when bureaucratic data becomes real-time power. Whether that power is used to protect society or quietly reshape it depends less on code than on courage—courage to regulate, to audit, and to say no.

The technology is already here.

The question is whether democracy is ready for it.