I used to believe privacy was simply part of the deal. You lived your life, obeyed the law, and your personal world stayed personal. Your conversations, your movements, your associations — those belonged to you. Somewhere along the line, that assumption stopped being safe.

That illusion finally collapsed when the scope of modern surveillance was dragged into the light.

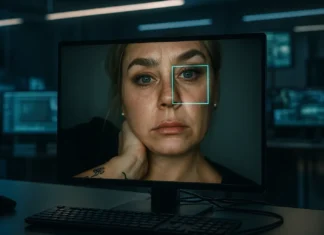

What was revealed wasn’t a single rogue program or an isolated abuse of power. It was an ecosystem — a sprawling surveillance architecture built to collect first and justify later. Systems like PRISM exposed how intelligence agencies gained access to private communications stored on corporate servers. Tools such as XKEYSCORE showed how easily global internet activity could be searched and analyzed. Upstream collection demonstrated that the internet’s physical backbone itself had become a surveillance surface. Phone metadata programs proved that you don’t need content to map a life — patterns are enough.

These weren’t surgical instruments. They were drag nets.

What unsettles me now is not just that these programs existed, but how naïve it would be to believe they simply stopped. Surveillance infrastructure doesn’t get dismantled; it gets renamed, reorganized, and quietly folded into new legal frameworks. Oversight tightens just enough to calm the public, while the machinery keeps running.

It’s far more realistic to assume that many of these capabilities continue under different program names, different authorities, and increasingly, different partners. Today’s surveillance state doesn’t rely solely on government-built systems. It leans heavily on private platforms — companies that already collect oceans of personal data as part of their business model. When governments want insight at scale, they don’t always need to spy directly. They can request, purchase, compel, or “partner.”

That’s where corporations like Amazon, Meta, and Google enter the picture. These firms operate the cloud infrastructure, social platforms, ad networks, and data pipelines that modern life runs on. Even when they claim resistance, the reality is that data already collected is data that can be accessed, correlated, or repurposed. Surveillance doesn’t always wear a badge anymore. Sometimes it comes wrapped in terms of service and API agreements.

Privacy is often misunderstood as secrecy. It isn’t. Privacy is control — the ability to decide who knows what about you, and for what purpose. Once that control is gone, other freedoms weaken alongside it. Speech becomes cautious. Association becomes selective. Dissent becomes something you calculate instead of exercise.

History makes the pattern obvious. Surveillance powers rarely remain confined to their original targets. They expand. They drift. They get reused during moments of fear or political pressure. And they tend to fall hardest on journalists, activists, minorities, and people who challenge prevailing power structures.

The most dangerous element here isn’t malice. It’s normalization. When constant monitoring becomes the background noise of modern life, the presumption of innocence quietly dissolves. You stop being a citizen first and become a dataset first.

Defending privacy today isn’t nostalgia for a vanished past. It’s realism about how power behaves when left unchecked. A free society doesn’t survive on trust alone. It survives on limits — limits on surveillance, limits on secrecy, and limits on how closely governments and corporations are allowed to intertwine.

The uncomfortable truth is this: mass surveillance didn’t disappear after it was exposed. It matured. And once surveillance becomes normal, privacy doesn’t vanish overnight. It erodes quietly — until one day you realize it’s already gone.